Examining Inventive Step in Australia

Navigating the nuances of inventive step (i.e., obviousness) requirements across global patent systems demands precision and adaptability. As jurisdictions refine their approaches to balancing innovation incentives with public access, practitioners must remain vigilant to avoid costly missteps in portfolio strategy. This series explores these critical distinctions through country-specific analyses, beginning with Australia’s evolving framework. In this jurisdiction, three distinct inventive step standards (as well as an innovative step standard) coexist based on filing dates and examination timelines.

Introducing the Inventive Step Series

This series dissects inventive step doctrines through a practitioner’s lens, comparing how different legal systems define and apply non-obviousness thresholds. We launch with Australia for its unique tripartite standard system and because its courts have shaped global patent jurisprudence through landmark decisions on combination patents and problem-solution approaches. Subsequent installments will analyze the approaches of key jurisdictions to prior art combinations, skilled person definitions, and the weighting of secondary indicia.

The evolution of obviousness in Australia

An invention will be taken to involve an inventive step in Australia unless it would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art (PSA) in light of the common general knowledge (CGK) and the relevant prior art base.[1] Currently, three different inventive step standards apply to existing patents and patent applications in Australia, depending on when the application was filed or when its examination was requested.

Inventive step: three ways

Applications filed on or after 30 April 1991 but before 1 April 2002 (Standard 1)

For applications filed from the commencement of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) on 30 April 1991 and prior to 1 April 2002, the assessment of inventive step is based on the CGK in the patent area only (i.e., Australia), optionally combined with a single piece of prior art information. The prior art information can be a single document or a single act that was made publicly available anywhere in the world before the priority date, provided the PSA could be reasonably expected to have “ascertained, understood and regarded [the prior art information] as relevant to work in the relevant art in the patent area”.

Under Standard 1, it is not possible to combine or “mosaic” documents to assess inventive steps unless the PSA in Australia treats them as a “single source of information.”

While Standard 1 is now more than twenty years old, it still applies to some pharmaceutical patents that have been extended under Australia’s patent term extension (PTE) provisions. However, as of 1 April 2027, it will no longer apply to any patents.

Applications filed on or after 1 April 2002 with examination requested before 15 April 2013 (Standard 2)

For applications filed from 1 April 2002, but for which examination was requested before 15 April 2013, the assessment of inventive step is based on the CGK in Australia, optionally combined with one or more pieces of prior art information, being documents or acts that were made publicly available anywhere in the world before the priority date.

It is also necessary under Standard 2 that the prior art information could be reasonably expected to have been “ascertained, understood and regarded as relevant” by the PSA to work the invention (although this is no longer limited to working the invention in Australia). In the case of combinations of documents, the PSA must also be reasonably expected to have combined them.

Applications with examination requested on or after 15 April 2013 (Standard 3)

For all applications for which examination was requested on or after 15 April 2013, the assessment of inventive step is based on the worldwide CGK, optionally combined with one or more pieces of prior art information, being documents or acts that were made publicly available anywhere in the world before the priority date.

It is no longer required that the prior art information be reasonably expected to have been “ascertained, understood, and regarded as relevant” by the PSA. Still, in the case of document combinations, it remains a requirement that the PSA be reasonably expected to have combined them.

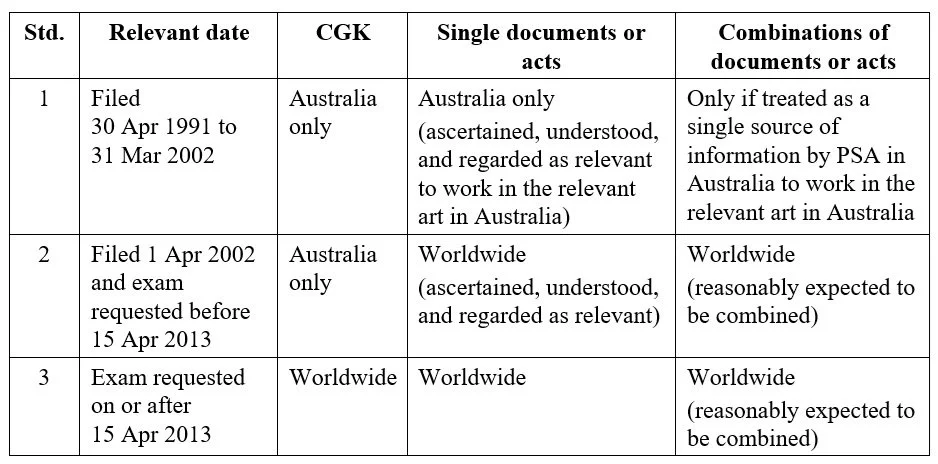

Summary of inventive step standards

Inventive step Standards 1-3 are summarized in the table below.

Tests for inventive step

The High Court (Australia's highest appellate court) has set out several tests for assessing inventive step. In Wellcome Foundation Ltd [1981] HCA 12, Aickin J posed the following test:

…whether the hypothetical addressee faced with the same problem would have taken as a matter of routine whatever steps might have led from the prior art to the invention, whether they be the steps of the inventor or not.

The High Court in Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2002] HCA 59 considered that steps taken “as a matter of routine” do not include “a course of action which was complex and detailed, as well as laborious, with a good deal of trial and error, with dead ends and the retracing of steps”. In that case, the High Court endorsed the following test for inventive step, which typifies the test applied by the Australian Patent Office and courts when the invention addresses a problem to be solved:[2]

Would the notional research group at the relevant date, in all the circumstances … directly be led as a matter of course to try [the claimed invention] in the expectation that it might well produce a [useful desired result]?

Thus, it is not enough that the claimed invention be “obvious to try”; the CGK considered separately or together with the relevant prior art information must directly lead the skilled person to the claimed invention with a reasonable expectation of successfully solving the problem.

The Full Federal Court recently considered what constitutes a “reasonable expectation of success” in the context of clinical trials in Sandoz AG v Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH [2024] FCAFC 135, which concerned Bayer's claims to rivaroxaban (Xarelto®). A prior patent publication disclosed rivaroxaban as the “lead candidate" for the treatment and prophylaxis of thromboembolic disorders based on in vitro data, and the efficacy of rivaroxaban was later confirmed in clinical trials, which formed the basis of the patent claims. In the absence of evidence that there was a “particular problem, difficulty or issue overcome” in taking that compound through pre-clinical and clinical trials, the claims were found to lack an inventive step. The Full Court noted that “the need to carry out clinical trials and other tests to obtain relevant data can be regarded as routine work consistent with a finding of obviousness”.

In assessing the inventive step of claims directed to combinations of known integers, the High Court in Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) [1980] HCA 9 stated:

In the case of a combination patent the invention will lie in the selection of integers, a process which will necessarily involve rejection of other possible integers. The prior existence of publications revealing those integers, as separate items, and other possible integers does not of itself make an alleged invention obvious. It is the selection of the integers out of, perhaps many possibilities, which must be shown to be obvious.

The purpose of the inventive step assessment is “looking forward from the prior art base to see what a person skilled in the relevant art is likely to have done when faced with a similar problem which the patentee claims to have solved with the invention”.[3] In other words, ex post facto or hindsight analysis must be avoided.

Starting point for assessing inventive step

The correct “starting point” for the assessment of inventive step was considered by an enlarged five judge bench of the Full Federal Court in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 99. The claims at issue related to use of a statin compound, rosuvastatin, for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia at a particular dosage. Statins were known to treat hypercholesterolemia at the priority date, but rosuvastatin was not considered to form part of the CGK or to be prior art information.

The primary judge considered that “the terms of the specification and claims inform the identification of the relevant starting point for the assessment of obviousness”. Thus, the claims were found to lack an inventive step in light of the CGK alone because the specification “pre-supposes the existence of rosuvastatin” and “the invention involved nothing more than the identification of a conventional starting dose for a compound within a known class for a known purpose”. However, the Full Court overturned the findings of the primary judge on the “starting point” issue, stating:

… it is apparent that the relevant provisions of the Act do not expressly or impliedly contemplate that the body of knowledge and information against which the question whether or not an invention, so far as claimed, involves an inventive step is to be determined may be enlarged by reference to the inventor’s (or patent applicant’s) description in the complete specification of the invention including, in particular, any problem that the invention is explicitly or implicitly directed at solving.

Thus, it is only if the information provided in the specification can be attributed to the PSA (i.e., forms part of the CGK) that it may be used as a starting point for assessing inventive step. In other words, where a patent is directed to the solution to a problem, the problem the invention solves must be discernible from the CGK and/or the relevant prior art base for knowledge of the problem to be attributed to the PSA as the starting point for assessing inventive step.

Selection of prior art documents

Single prior art document (Standard 1)

The election of a single prior art document for assessing inventive step under Standard 1 was also considered in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30. In that case, the High Court concluded that, provided the skilled person ultimately arrives at a single piece of prior art information that meets the relevant criteria to impart the information that is to be added to the CGK, there is nothing to stop them from using multiple documents to arrive at that one document.

Further, multiple documents may be identified, but each document must be considered separately, one at a time, together with the CGK. As a result, for the purposes of Standard 1, an invention may be rendered obvious by the combination of one document with the CGK, even if one or more other documents when combined with the CGK would teach away from the invention.[4]

Single source of information (Standard 1)

While there is very little case law in connection with a “single sources of information”, the circumstances under which two or more documents can be treated as a single source of information (albeit in the context of novelty) were considered by the Full Federal Court of Australia in Nicaro Holdings Pty Ltd v Martin Engineering Co [1990] FCA 40; (1990) 16 IPR 545. In that case, the Full Court considered two patent documents could form a single source of information where one in incorporated into the other by cross-reference “solely as a shorthand means of incorporating a writing disclosing the invention”.

As to what may constitute a single source of information more generally, the Full Court in Nicaro Holdings noted that much will depend upon the nature of the art and the degree of connection that exists between the documents. Essentially, documents (or acts) may be treated as a single source of information where they can be considered “one consistent whole”.

Ascertained, understood and regarded as relevant (Standards 1 and 2)

The requirements for a document (or act) to be reasonably expected to have been “ascertained, understood and regarded as relevant” by the PSA was also considered the High Court in Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd [No 2] [2007] HCA 21. The High Court explained the relevant terms as follows:

“ascertained” means discovered or found out (e.g., by routine or conventional searches);

“understood” means that, having discovered the information, the skilled person would have comprehended it or appreciated its meaning or import; and

“relevant to work in the relevant art” means publicly available information, not part of the common general knowledge, that the PSA could be expected to have regarded as relevant to solving a particular problem, or meeting a long-felt want or need, as the patentee claims to have done.

For the purpose of Standard 1, this requirement is further qualified in that the document (or act) must be reasonably expected to have been “ascertained, understood and regarded as relevant to work in the relevant art in the patent area”. This means that, if there was nobody working in the relevant field in Australia at the priority date, no documents or acts with respect to that field can be taken into account for assessing inventive step.

The Full Federal Court also considered what constitutes "reasonable ascertainment" in Sandoz, stating: “It is not necessary for evidence to be adduced that the skilled person would prefer, prioritise or select the information in question … over all other information which they could be reasonably expected to have discovered or found out, including other information which was not adduced into evidence”. Rather, it was considered enough to establish reasonable ascertainment that any search results adduced into evidence “are a subset of the searches which would have been taken by the skilled person”.

Combinations of documents (Standards 2 and 3)

There is also limited case law on when two or more documents (or acts) may be reasonably expected to have been combined by the PSA. However, the Australian Patent Office has included some guidance in its Patent Manual of Practice and Procedure as to factors that may be relevant as follows:[5]

whether the nature and content of the documents are such as to make it likely or unlikely that the PSA would combine them;

whether the documents (or acts) come from similar, different or remote technical fields; and

whether the art would have taught away from a particular solution or combination at the priority date.

Practical considerations during prosecution

In assessing inventive step, the Australia Patent Office favours a problem-solution approach. This approach involves:[6]

(i) construing the specification to determine the problem the invention solves;

(ii) identifying the relevant PSA;

(iii) determining whether, in the context of the problem, any pieces of prior art information under consideration could be reasonably expected to have been combined by the PSA;

(iv) determining the CGK; and

(v) determining whether, in the context of the problem, the claimed invention would have been obvious to the PSA.

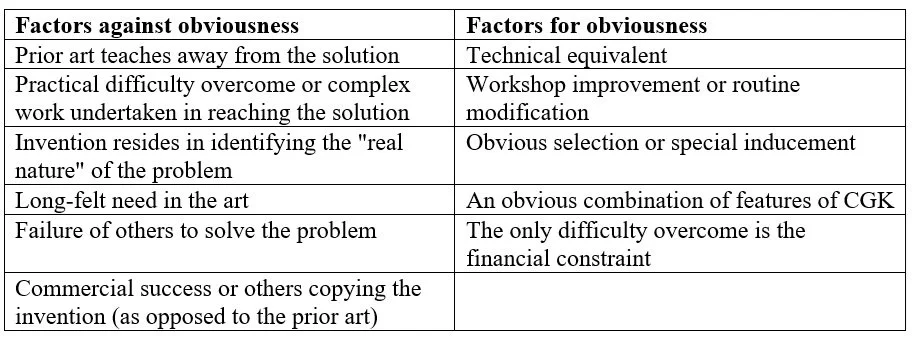

Step (v) typically involves applying one or more of the tests for inventive step mentioned above. The Patent Office (and courts) may consider several other factors that could weigh for or against the invention being deemed obvious. Examples of these factors are provided in the following table.

While the factors against obviousness (or secondary indicia) mentioned above are not determinative of an inventive step, evidence of these factors may assist in establishing that an invention would not be obvious to the PSA.

The innovative step standard

To complicate matters further, Australia also has a second-tier innovation patent system — the innovation patent system — the phasing out of which began on 26 August 2021 (with the last of the innovation patents to expire in August 2029). Innovation patents have a maximum term of 8 years and can contain only five claims, with a grant readily obtained within about one month of filing provided certain formalities requirements are met. However, substantive examination and certification is required to enforce an innovation patent.

Relevantly, the claims of an innovation patent need only rise to the level of an “innovative step”, i.e., make a substantial contribution over the prior art, which is a much lower standard than any of the "inventive step" standards mentioned above (and, consequently, are more difficult to invalidate). While it is no longer possible to file new standalone innovation patents, it is still possible to file divisional innovation patent applications from standard patent applications that have an effective filing date before 26 August 2021, provided the standard patent application is still pending and, if accepted (allowed), within three months of the date of advertisement of acceptance.

Final Thoughts: Strategic Considerations for Practitioners

Australia’s phased standards demand time-machine-like analysis when handling legacy portfolios. Five key action points emerge:

1. Timeline Audits

• Map all pending/appealed cases against the 1 April 2027 sunset clause for Standard 1

• Consider whether divisional claims subject to a higher inventive step standard can be incorporated into a parent patent subject to a lower standard (e.g., by narrowing post-grant amendments) to strengthen against third-party challenges

• Consider whether it is possible to file a divisional innovation patent application to strengthen against third-party challenges

2. CGK Boundaries

• For Standard 1/2 cases, commission Australian-specific CGK analyses from local experts

• Standard 3 case requires global CGK mapping

3. Combination Defense

• Preemptively document technical disincentives against prior art combinations

• Consider whether mosaicking or combining documents as a single source of information is permitted under the relevant standard and, in the latter case, whether documents can be treated appropriately as a single source of information

4. Problem-Solution Alignment

• Where possible, draft specifications to mirror CGK-recognized problems, avoiding (or in addition to) self-created technical narratives

• Use experimental data tables to cement "non-routine" research pathways

5. Secondary Indicia Leverage

• Systematically document any practical difficulties, long-felt need, and unexpected synergies during development, drafting, and prosecution

• Leverage thresholds to meet reasonable "ascertainment" and "relevance" requirements in Standard 1/2 cases

As Australia’s patent landscape converges with global norms, practitioners must bridge historical precedents with emerging trends, particularly in the life sciences, where extended terms prolong the applicability of Standard 1. The forthcoming 2027 transition presents both challenges and opportunities for portfolio optimization through strategic divestments and asset repositioning.

This post was prepared by Lisa Mueller and Claire Gregg of Davies Collison Cave

[1] Patents Act 1990 (Cth), s 7(2)

[2] First set out in Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation v Biorex Laboratories Ltd [1970] RPC 157 at 187–188 per Graham J, referred to as a reformulation of the "Cripps question" set out in Sharp & Dohme Inc v Boots Pure Drug Company Ltd (1928) 45 RPC 153 at 173

[3] Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd [No 2] [2007] HCA 21

[4] As was the case in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30

[5] Section 5.6.6.2

[6] Conveniently summarised in the Australian Patent Office Manual of Practice and Procedure at sections 5.6.6.4 and 5.6.6.5