Federal Circuit Reverses Jury Verdict: Allergan's Latisse Patent Claims Invalid for Lack of Written Description in Duke University v. Sandoz Inc.

Introduction

On November 18, 2025, the Federal Circuit delivered a significant decision reversing a District Court jury verdict and finding claim 30 of U.S. Patent No. 9,579,270 invalid for lack of adequate written description. In Duke University v. Sandoz Inc., 24-1078, the Court grappled with fundamental questions about how broadly a patent specification may be drafted when claiming a genus of chemical compounds, particularly in the pharmaceutical space. The case serves as a stark reminder that casting a wide net in the specification while attempting to claim a narrow subgenus can prove fatal under the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112(a), even when a jury initially finds the patent valid.

This dispute arose from Sandoz's manufacture and sale of a generic version of Allergan's blockbuster product, Latisse®, an FDA-approved topical treatment for eyelash hair loss that contains bimatoprost. Despite Sandoz stipulating to infringement and a jury awarding Allergan $39 million in damages after finding the patent valid, the Federal Circuit held that no reasonable juror could have concluded otherwise than that the patent failed to adequately describe the claimed invention.

Patent at Issue

The patent at the center of this litigation is U.S. Patent No. 9,579,270 (the "'270 patent"), which issued in 2017 with a 2000 priority date. The patent is entitled "Compositions and Methods for Treating Hair Loss Using Non-Naturally Occurring Prostaglandins," and relates generally to treating hair loss using compositions containing prostaglandin F ("PGF") analogs.

Duke University and Allergan Sales, LLC together own all rights in the '270 patent and certain related patents. While the decision mentions "certain related patents," the appeal and analysis focused exclusively on claim 30 of the '270 patent.

The Technology

The '270 patent describes methods for growing hair through the topical application of specific chemical compounds known as prostaglandins. As the District Court explained in language adopted by the Federal Circuit:

"The '270 Patent describes a method for growing hair by topically applying a chemical compound known as a prostaglandin. Prostaglandins are molecules that bind to certain receptors on cells in a living body and change how such cells function. The human body produces a variety of prostaglandins; the general type at issue here is known as prostaglandin F or PGF. Within the general category of PGF are many variants, some naturally-occurring and some synthesized. These variants are referred to as PGF analogs. Analogs differ from one another by virtue of various molecules that can attach to [the] base structure of the prostaglandin and which change its pharmacological properties. For example, the prostaglandin is much like a charm bracelet to which different charms can be attached at different points."

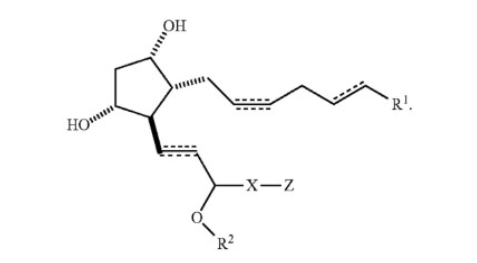

The technology centers on PGF analogs, chemical variants of prostaglandin F that differ based on which molecules attach to the prostaglandin base at various positions. These structural variations alter the pharmacological properties of the compounds. The key structural elements include:

The Prostaglandin Hairpin Structure: This represents the basic carbon skeleton shared by all prostaglandins, a generic structural feature common to billions of potential compounds. Both parties' experts agreed at trial that this characteristic hairpin structure, including a linker, formed the foundational backbone of the compounds.

The C1 Position (R1 Position): Also called the "action end," this critical position on the molecule could accommodate various functional groups. The specification disclosed 13 categories of options for this position, though, as the Federal Circuit noted, most of these categories contain numerous subcategories that required additional choices.

The Omega End (Z Position): This represented the opposite end of the molecule from the C1 position. The specification disclosed eight broad categories of options for the Z position, including carbocyclic groups, heterocyclic groups, aromatic groups, and their substituted variants.

The X Position (Linker): This connected different portions of the molecule and could be selected from up to 15 different structural options.

Additional Variable Positions: The specification also described variability at the R2, R3, R4, and Y positions, each offering multiple options or requiring selection from categorical choices.

The commercial embodiment at issue was bimatoprost, the active ingredient in Allergan's Latisse® product. Bimatoprost is a PGF analog specifically characterized by an ethyl amide at the C1 position and a phenyl group at the omega (Z) position. Latisse® consists of a 0.03% bimatoprost ophthalmic solution and represents an FDA-approved treatment for eyelash hypotrichosis (inadequate or insufficient eyelashes).

The technological challenge highlighted by this case involved the enormous chemical space encompassed by the patent's broad specification. Experts agreed that when considering all possible combinations of substituents that could fill the various positions on the prostaglandin backbone as described in the specification, the patent potentially encompassed billions of compounds. In stark contrast, claim 30, the specific claim at issue, was directed to a far narrower subset of between 1,620 and 4,230 compounds, depending on which expert's calculation one accepted.

Representative Claims Involved in the Litigation

The sole claim at issue in this appeal was claim 30 of the '270 patent. This claim is a dependent claim that must be read together with claims 17, 24, and 25, from which it depends. The Federal Circuit reproduced the full text of claim 30 (when read with its parent claims) as follows:

"A method of growing hair, wherein the method comprises topically applying to mammalian skin a safe and effective amount of a composition comprising:

. . . an active ingredient selected from the group consisting of a prostaglandin F analog of the following structure:

and pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof;

wherein R1 is C(O)NHR3 [i.e., an amide];

R2 is a hydrogen atom;

R3 is methyl, ethyl, or isopropyl;

X is selected from the group consisting of —C≡C—, a covalent bond, —CH=C=CH—, —CH=CH—, —CH=N—, —C(O)—, —C(O)Y—, and —(CH2)n—, wherein n is 2 to 4;

Y is selected from the group consisting of a sulfur atom, an oxygen atom, and NH; and

Z is phenyl."

During the District Court proceedings, a jury found this claim not invalid for obviousness, lack of enablement, or lack of adequate written description, but the Federal Circuit reversed on the grounds of a lack of written description.

Procedural History at the District Court

The litigation commenced in 2018 when Allergan sued Sandoz in the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado (Judge Raymond P. Moore presiding), alleging that Sandoz's generic version of Latisse® infringed claim 30 of the '270 patent. Rather than contesting infringement, Sandoz stipulated infringement but mounted a robust challenge to the validity of claim 30.

The case proceeded to a five-day jury trial where the central battleground was the validity of claim 30 under three separate grounds: obviousness, lack of enablement, and lack of adequate written description.

Sandoz's Case: Sandoz presented the expert testimony of Dr. Clayton Heathcock, who opined that claim 30 lacked sufficient written description because "the claim describes over 4,000 compounds that can cause hair to grow," but the specification does not identify "a single" specific embodiment of the claim and failed to disclose sufficient common structural features of the compounds encompassed by the claim.

Allergan's Defense: Allergan countered with its own expert, Dr. Allen Reitz, who testified that the '270 patent "adequately describes the use of amides for growing hair . . . with three types of prostamides with a phenyl ring at the end of the omega chain."

After hearing all the evidence, the jury found in favor of Allergan, concluding that Sandoz had failed to prove that claim 30 was invalid for obviousness, lack of enablement, or lack of adequate written description. The jury awarded Allergan $39 million in infringement damages.

Following the jury’s decision, Sandoz filed post-trial motions for a new trial and for judgment as a matter of law, arguing that the evidence could not support the jury's verdict on validity. The district court denied both motions.

Sandoz then timely appealed to the Federal Circuit.

Key Issues on Appeal

While Sandoz raised multiple issues in its appeal, the Federal Circuit determined that it needed to address only one dispositive question: whether the District Court erred in denying Sandoz's motion for judgment as a matter of law that claim 30 of the '270 patent is invalid for lack of adequate written description.

The written description requirement, codified at 35 U.S.C. § 112(a), mandates that "[t]he specification shall contain a written description of the invention." The legal standard requires that the patent specification disclose sufficient information such that a person of ordinary skill in the art would conclude "the inventor possessed the full scope of the invention" at the time of the patent application.

Sandoz's core argument centered on the vast disparity between the broad genus described in the specification and the narrow subgenus claimed. Specifically, Sandoz contended that:

The specification of the '270 patent was written so broadly that it encompassed a "universe of billions of compounds";

Claim 30, in contrast, was limited to approximately 1,620 compounds (per Sandoz's expert) or roughly 4,230 compounds (per Allergan's expert);

The patent failed to provide skilled artisans with adequate "blaze marks" or guidance to identify and navigate from the broad billions of compounds described in the specification down to the specific subgenus of 1,620-4,230 compounds actually claimed;

The specification failed to provide even a single working example of a compound that falls within claim 30; and

The specification failed to identify sufficient structural commonalities that would allow a skilled artisan to visualize or recognize the claimed subgenus.

For a genus claim of chemical compounds, Federal Circuit precedent requires the specification to describe "not only the outer limits of the genus but also of either a representative number of members of the genus or structural features common to the members of the genus, in either case with enough precision that a relevant artisan can visualize or recognize the members of the genus."

As will be discussed in more detail herein, Allergan conceded that the patent did not satisfy the "representative number" test, as the specification did not expressly disclose even a single embodiment that fell within claim 30. Therefore, the entire dispute focused on whether the specification satisfied the alternative "common structural features" test.

Allergan argued that the specification adequately described three structural features common to all members of the claimed subgenus: (i) the characteristic prostaglandin hairpin; (ii) amides at the C1 position; and (iii) an unsubstituted phenyl ring at the omega (Z) end.

Other issues raised but not reached: Because the Federal Circuit found claim 30 invalid for lack of written description, it did not need to address Sandoz's other principal arguments, which included: (1) whether Allergan should have been collaterally estopped from litigating its obviousness defense due to prior Federal Circuit decisions; (2) whether the district court's jury instruction on "teaching away" was prejudicially flawed; and (3) whether claim 30 failed the enablement requirement.

Federal Circuit Findings and Holdings

The Federal Circuit, in an opinion authored by Circuit Judge Stark and joined by Circuit Judges Dyk and Stoll, reversed the District Court's judgment, holding that claim 30 of the '270 patent was invalid for lack of adequate written description.

The Core Holding

The Court held that "no reasonable juror could have found that Sandoz failed to prove, by clear and convincing evidence, that claim 30 lacked adequate written description." In other words, the deficiencies in the written description were so clear that the jury's verdict could not stand.

The Court grounded its holding in fundamental patent law principle: "The written description requirement reflects the basic premise of the patent system[:] an inventor may obtain[] a patent only if she discloses [the] invention to the public, in sufficient enough detail that a person of ordinary skill in the art will understand that the inventor truly possessed the invention as claimed." The requirement serves "to prevent an applicant from later asserting that he invented that which he did not."

The Specification-Claim Disparity

The Federal Circuit began its analysis by establishing certain uncontested premises. Both parties' experts agreed, and therefore any reasonable juror had to accept that:

The specification was written in such a broad manner, with multiple open positions on its chemical structure that could be filled in various ways, that it encompassed billions of compounds;

The number of compounds claimed in claim 30 was far smaller: either 4,230 (Allergan's expert's view) or 1,620 (Sandoz's expert's opinion); and

Therefore, the specification broadly describes billions of compounds, whereas claim 30 targets only between 1,620 and 4,230 of those compounds.

Given this vast disparity, "the specification of the '270 patent needs to allow a skilled artisan to understand how to identify this subgenus of claimed compounds" from among the billions described.

The Legal Framework for Genus Claims

The Federal Circuit emphasized that for patents claiming a genus of chemical compounds, the specification must provide sufficient indication of "how a skilled artisan would narrow the disclosed universe of billions of compounds described in the specification to the subset of just 1,620-4,230 compounds actually claimed."

The Federal Circuit reaffirmed its two-part test: the specification must describe "either (i) a representative number of species of claim 30's subgenus or (ii) structural features common to all members of that subgenus."

The Representative Number Alternative: Allergan conceded it could not satisfy this first alternative. The '270 patent "does not expressly disclose even a single embodiment of claim 30." For example, the Court noted that the only disclosed embodiment containing C(O)NHR3 at the C1 end and phenyl in the Z position did not contain methyl, ethyl, or isopropyl in the R3 position, "thus falling outside of claim 30." The jury instructions were limited to the common structural features test, and the parties discussed at trial that "there's been no evidence that th[e] . . . theory" of representative number applies.

The Common Structural Features Alternative: This became the sole basis for Allergan's defense. To satisfy written description through this route, "the patent must 'provide sufficient blaze marks' to direct a skilled artisan to the claimed subgenus." The specification must "provide[] adequate direction which reasonably would lead persons skilled in the art to" the compounds actually claimed in claim 30.

Analysis of Allergan's Three Proposed Common Features

Allergan insisted the specification adequately disclosed three features common to the claimed subgenus: (i) the prostaglandin hairpin; (ii) amides at the C1 position; and (iii) an unsubstituted phenyl ring at the omega end. The Federal Circuit systematically dismantled each of these arguments.

The Prostaglandin Hairpin: The Court found this structural feature fatally generic. It was "undisputed at trial that this is a 'generic' feature." Both parties' experts agreed that the hairpin represented "the basic carbon skeleton of all prostaglandins." Dr. Reitz, Allergan's expert, admitted that "billions of compounds are represented by th[e] backbone."

The critical flaw: "Allergan failed to identify how this common structural feature was unique to the claimed subgenus, as opposed to the entire genus described in the specification." Because the hairpin structure was shared by billions of compounds, it provided no meaningful guidance for narrowing to the thousands of compounds in claim 30. The Court concluded: "Allergan has not introduced evidence to show that a person of ordinary skill in the art would be able to 'visualize' the thousands of compounds claimed in claim 30, from among the billions of prostaglandin compounds described in the specification, based on the written description of the widely shared hairpin structure."

The C1 Position (Amide Selection): The Court's analysis of the C1 position proved particularly damaging to Allergan's case. Allergan argued that "the specification undisputedly discloses only 13 options for [the C1] action end," with one being the claimed amide, C(O)NHR3. The Federal Circuit flatly rejected this characterization as "not correct."

The Court explained that the specification taught:

"R1 is selected from the group consisting of C(O)OH, C(O)NHOH, C(O)OR3, CH2OH, S(O)2R3, C(O)NHR3, C(O)NHS(O)2R4, tetrazole, a cationic salt moiety, a pharmaceutically acceptable amine or ester comprising 2 to 13 carbon atoms, and a biometabolizable amine or ester comprising 2 to 13 carbon atoms."

While superficially appearing as "13 options," a skilled artisan would understand that only four of these (C(O)OH, C(O)NHOH, CH2OH, and tetrazole) are singular items; the other nine are categories, each requiring additional choices. The Court characterized this structure vividly: "the specification's guidance with respect to the C1 position resembles a path with 13 branches, and most of those branches lead to additional branches, yielding in the end a vast number of options for C1."

Taking the example of C(O)NHR3 itself, option number 6 on the list and the choice required to reach claim 30, the Court observed that "the inclusion of the substituent R3 as a component of this option requires a further choice to be made." The specification discloses no fewer than 12 further categories from which the artisan must select to fill the R3 position. One of those 12 categories alone, the "heterogenous group", was defined as "a saturated or unsaturated chain containing 1 to 18 member atoms," which might be straight or branched in multiple spots, with or without double and triple bonds.

The Court emphasized: "even assuming a person of ordinary skill chose C(O)NHR3 from among the '13 options' for C1, just to fill in the C1 position she would still have to (i) select 1 of 12 categories for the R3 position, and then (ii) select a specific molecule from whichever category of those 12 she chose."

This maze-like structure proved fatal. The Federal Circuit invoked its precedent: "Following [such a] maze-like path, each step providing multiple alternative paths, is not a written description of what might have been described if each of the optional steps had been set forth as the only option." The court quoted its own memorable language from Purdue Pharma L.P v. Faulding, Inc., 230 F.3d 1320, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2000): "one cannot disclose a forest in the original application, and then later pick a tree out of the forest and say 'here is my invention.'" Instead, adequate written description "requires disclosure of sufficient 'blaze marks directing the skilled artisan to that tree.'"

The Misdirection of "Preferred" Embodiments: Making matters worse for Allergan, the Court found that "the only blaze marks provided by the specification for this C1 selection point away from the combinations as recited in claim 30." The specification identifies five of its 13 options for C1 as either "prefer[red]" or "more prefer[red]"—but these five did not include C(O)NHR3, which is precisely what a skilled artisan would need to choose to reach the claimed invention.

The Court concluded: "This means that the 'preferred' and 'more preferred' blaze marks direct a skilled artisan away from, rather than toward, the claimed subgenus, which would again lead the artisan to conclude the inventors did not actually possess what they claimed." Dr. Heathcock, Sandoz's expert, testified that the specification described carboxylic acid and esters as more preferred and did not note any preference for C1-alkylamides like bimatoprost.

The Court acknowledged that once an artisan chose the non-preferred C(O)NHR3 path, the specification provided some help by teaching that R3 "is preferably . . . selected from the group consisting of methyl, ethyl, and isopropyl." But this created a logical inconsistency: "Allergan has not identified any persuasive reason why an artisan who ignored the first set of blaze marks, effectively directing her away from C(O)NHR3, would then follow the blaze marks given for the R3 location of this non-preferred group."

Synthesis Examples: Allergan also cited portions of the specification that teach methods for compound synthesis, including four examples of synthesizing compounds containing amides, and argued that this would have steered a skilled artisan toward placing an amide at C1. The Court was unpersuaded. In each of the four synthesis schemes, "C1 can be any of the same variants listed above, that is, any of the '13 options,' nine of which are categories requiring further embedded choices, but one ends up with an amide only if one selects option number six from that list, C(O)NHR3." Even the formulas calling out amides as examples "do not indicate that amides should be preferred at C1." Additionally, Dr. Reitz admitted that two specific examples in the synthesis schemes using sulphonamides or hydroxamic acid were not within the scope of the '270 patent's claims.

The Z Position (Phenyl Selection): The Court's analysis of the omega end position proved equally problematic for Allergan. While Allergan contended "the specification discloses only eight categories of options for Z, and . . . expresses a preference for phenyl," the Court noted that "each of these eight categories required additional embedded choices."

The specification taught: "Z is selected from the group consisting of a carbocyclic group, a heterocyclic group, an aromatic group, a heteroaromatic group, a substituted carbocyclic group, a substituted heterocyclic group, a substituted aromatic group, and a substituted heteroaromatic group."

The specification did identify phenyl as "the most preferred aromatic group," but the Court found "this guidance was only pertinent once the artisan selects an aromatic group from among the eight initially described options, which nothing in the specification directs such an artisan to do." Dr. Reitz explained that when "Z is selected from an aromatic group," a skilled artisan would know phenyl is an aromatic group and the most preferred one, "but [could] not identif[y] a reason why an artisan would select an aromatic group in the first place."

Allergan argued that "at least ten of the patent's example compounds employ unsubstituted phenyl at the omega end." The Court found this unpersuasive: "The specification lists 95 example compounds and gives no reason to prefer the ten examples containing phenyl." Moreover, "ten is not even the greatest number of appearances of a compound at the omega end; flurobenzene is used at Z in 18 of the 95 example compounds disclosed in the patent."

The Court also addressed a conditional preference buried in the specification: phenyl is preferred when "Z is selected from among a 'group consisting of furanyl, thienyl, and phenyl,'" but this guidance only applies if the artisan has already chosen a —C≡C— bond for the X position. Such a bond "is just one of as many as 15 options for X," and "is the only one that, if selected, contains a blaze mark pointing to phenyl." Therefore, "the skilled artisan must first reach a conclusion regarding X, the linker, before the specification may, but in most cases will not, prompt her to prefer phenyl."

The Court's Ultimate Conclusion

Synthesizing its analysis, the Federal Circuit concluded: "even accepting that the specification guides a skilled artisan towards the hairpin structure, leaving only variability at the C1 and Z ends to be navigated, the specification did not provide sufficient 'blaze marks' to guide a skilled artisan to a PGF analog with an amide at the C1 position and a phenyl at the Z position, which are both required elements of the compounds comprising claim 30's subgenus."

The Court invoked its precedent from Fujikawa v. Wattanasin, 93 F.3d 1559, 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1996): "the specification of the '270 patent does not 'direct one to the proposed tree in particular, and does not teach the point at which one should leave the trail to find it.'" Instead, "the specification may only reasonably be viewed as a mere 'laundry list' disclosure of every possible moiety for every possible position, making it inadequate to satisfy the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112(a)."

The Federal Circuit emphasized the exceptional nature of its reversal: "this is a case in which the appellant has overcome the doubly high burden of persuading us to overturn a jury verdict of no invalidity." The deficiencies were so clear that "the multiple, branching paths of the '270 patent's specification are clear on the face of the patent, were explained in detail by Sandoz's expert, and their existence was not disputed by Allergan's expert."

The Court held: "any reasonable juror would have found, by clear and convincing evidence, that a person of ordinary skill in the art, reviewing the specification of the '270 patent, would be unable to visualize or recognize the members of the subgenus claimed by claim 30 based upon the specification's disclosures." The specification "fails to provide the relevant artisan with sufficient blaze marks or structural commonalities among the claimed compounds to lead her to conclude that the inventor actually possessed the claimed invention."

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit reversed the judgment of the District Court, holding that claim 30 of the '270 patent is invalid for lack of adequate written description.

Key Takeaways

This decision offers several critical lessons for patent practitioners, particularly those working in the pharmaceutical and chemical arts:

1. The Forest-and-Tree Problem Remains Fatal: The Federal Circuit continues to strictly enforce the principle that patentees cannot "disclose a forest in the original application, and then later pick a tree out of the forest" without providing adequate blaze marks. When a specification describes billions of potential compounds through combinatorial selections, but the claims target only thousands, the specification must provide clear guidance, not just theoretical possibilities, for navigating from the broad to the narrow.

2. Generic Structural Features Provide Insufficient Support: Relying on structural features that are common to the entire disclosed genus, not just the claimed subgenus, will not satisfy the written description requirement. Here, the prostaglandin hairpin structure was shared by billions of compounds and provided no meaningful limitation pointing to the claimed subgenus. Common features must be distinctive to the claimed compounds, not merely present in them.

3. Categorical Choices Compound the Problem: Patent drafters must be acutely aware that offering choices among broad categories, where each category itself requires further selections, creates a "maze-like path" that fails to provide adequate written description. The Federal Circuit’s analysis of the C1 position is particularly instructive: what Allergan characterized as "13 options" was a branching tree of hundreds or thousands of possible selections. Each layer of categorical choice multiplies the complexity and obscures the path to the claimed invention.

4. "Preferred" Embodiments Must Point Toward, Not Away From, the Claims: When a specification identifies certain embodiments as "preferred" or "more preferred," these serve as critical blaze marks guiding the skilled artisan. If the preferred embodiments point away from the claimed invention, as occurred here when the specification preferred five options for C1 that did not include the claimed C(O)NHR3, this strongly suggests the inventors did not actually possess the claimed invention at the time of filing. Practitioners should ensure that preferred embodiments align with and support the intended claim scope.

5. Synthesis Examples Must Be Within Claim Scope: Allergan's reliance on synthesis examples proved unavailing when its own expert admitted that specific examples (using sulphonamides or hydroxamic acid) fell outside the scope of the claimed invention. Working examples in the specification should exemplify compounds that actually fall within the scope of the claims being pursued.

6. Statistical Presence Among Examples Is Insufficient: The fact that phenyl appeared in ten of 95 disclosed example compounds did not establish an adequate written description for requiring phenyl at the Z position. The court noted this was not even the most frequently appearing option (fluorobenzene appeared 18 times). Raw frequency without explanation or preference provides insufficient guidance to the skilled artisan.

7. Conditional Guidance Buried in Complex Selection Trees Is Inadequate: The specification's preference for phenyl when the artisan had selected an aromatic group (one of eight options for Z) and had separately chosen a —C≡C— bond for X (one of 15 options) exemplifies guidance so conditional and layered that it fails to provide meaningful direction. Blaze marks must be accessible and prominent, not contingent on multiple prior selections.

8. Lack of Any Working Example Within Claim Scope Is Highly Problematic: The '270 patent did not disclose even a single specific embodiment that fell within claim 30. While Federal Circuit precedent allows satisfying written description through either representative examples or common structural features, the complete absence of any working example placed enormous pressure on the common structural features analysis, pressure that the specification could not withstand.

9. The Blaze Marks Metaphor Matters: Federal Circuit jurisprudence increasingly employs the "blaze marks" metaphor drawn from Purdue Pharma and related cases. Practitioners should consciously consider whether their specifications provide clear trail markers guiding the skilled artisan from broad disclosures to specific claimed embodiments. This requires more than mere disclosure of components; it demands directional guidance.

The Duke v. Sandoz decision stands as a cautionary tale about the perils of overly broad specification drafting combined with narrow genus claiming in chemical and pharmaceutical patents. While maximizing flexibility through extensive variation may seem appealing during patent drafting, such an approach risks fatal written description deficiencies if the resulting claims target a specific subgenus without adequate specification support. The opinion reinforces that possession of an invention, as demonstrated through the written description, remains a foundational requirement of the patent system, one that cannot be satisfied through after-the-fact selection from an overly broad menu of possibilities.

This post was written by Lisa Mueller.