Seismic Shifts at the USPTO: Navigating Patent Practice in a New Era

Introduction

We stand at an inflection point in U.S. patent prosecution. The sweeping changes implemented at the United States Patent and Trademark Office in 2025 represent nothing short of a restructuring of patent examination practice as we have known it for decades. As patent practitioners with experience navigating evolving patent policy across diverse technical disciplines, we have weathered many storms in our careers. Still, the convergence of factors now at play demands that we fundamentally recalibrate our strategic approach to patent prosecution.

The purpose of this post is to distill, for colleagues in the patent bar, the major policy and practice changes that have unfolded at the USPTO as of November 2025. More importantly, we aim to translate these changes into actionable guidance for practitioners seeking to protect their clients' innovations in this new landscape, whether those innovations span biotech, pharmaceuticals, software, mechanical devices, or any other technological field. The terrain is shifting beneath our feet; understanding the contours of that shift is essential to maintaining an effective prosecution strategy across all technology areas.

The Four Major Dimensions of Change

Director Squires and the newly structured USPTO leadership have implemented changes across four critical dimensions:

Sweeping, unprecedented changes to patent examiner working conditions

Addressing the massive backlog of unexamined applications

A fundamental reframing of how 35 U.S.C. § 101 patent eligibility is applied

A historic recalibration of the quantity-versus-quality tension that has haunted the USPTO for 80 years

Each of these dimensions carries profound implications for prosecution strategy. Let us examine them in sequence.

Part 1: The Upheaval in Patent Examiner Working Conditions

The Scope of Change

Beginning on January 20, 2025, the new administration initiated sweeping changes to the USPTO's human infrastructure:

Revoked patent examiner job offers

Removed probationary employees, IT, clerical, and search support staff

Offered early retirement via the "Fork" memo (The “Fork” memo refers to the

Fork in the Road” program, which was an Office of Personnel Management (OPM) memo sent to federal employees, including those at the USPTO, in January 2025. The memo offered federal workers a voluntary option to resign with a deferred end date of September 30, 2025, providing severance payment and a period of paid administrative leave.)Hired a second tier of patent examiners (the new "Personalist" position)

Mandated in-office work for supervisors and new examiners

Curtailed training and mentoring opportunities

Shortened the patent training academy for 2025 hires

What followed was a series of management directives that fundamentally altered the working conditions and operational constraints under which examiners labor:

Redeployed supervisory staff: Supervisor Patent Examiners (SPEs) and Quality Assurance Specialists (QASs) were reassigned to examining Patent Backlog Applications (PBAs), with an explicit agreement that no quality review would be performed on PBAs.

Expanded SPE review burden: SPEs are now required to perform a 30-minute merits review of all rejected and allowed independent claims for every application in their art unit, a task mathematically incompatible with their existing workload. This second pair of eyes review is required for office actions prepared by both junior examiners and primary examiners. In contrast, prior quality reviewers had typically been given 3-4 hours to check randomly selected office actions for compliance with the statutory requirements.

Docket takeover mandates: SPEs must now assume and complete dockets previously handled by examiners who leave the agency.

Compressed interview time: Examiner time for applicant interviews has been limited to one hour per round of prosecution.

End of post-final procedures: The AFCP 2.0 after-final program expired in December 2024.

The “all-hands-on-docket” emphasis is providing first office actions on brand-new applications. Requests for Continued Examination (RCE) and continuing applications (divisional and continuations) have been moved to the back of the docket.

De-prioritization of Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) applications: Previously, a first office action was issued on average about 6-7 months after a PPH. Now, PPH applications will receive their first office action at about half the speed of non-expedited applications. This could be as long as 18 months in tech centers with massive backlogs.

Redefinition and restructuring: Patent examination work has been redefined as a national security function. Examiners have been removed from the Patent Office Professional Organization (POPA) union bargaining unit. Collective Bargaining Agreements, including the right to telework, are no longer in force. Performance and appraisal plans have been revised, and bonus structures fundamentally altered.

Commissioner Martin Wallace mandates that patent examiners screen patent applications for national security-related material.

AI-driven searching mandate: All examiners are required to perform AI-based similarity searches on every application.

USPTO management has not provided patent examiners with training or time to take training on these changes.

Is the USPTO edging towards an AI-driven patent registration system?

Perhaps most significant is the creation of a second tier of patent examiners—the "Personalist" examiner. These new hires have been assigned AI development tasks, suggesting that the USPTO envisions a hybrid human-machine examination process. The creation of two distinct examiner classes—traditional examiners and personalist examiners—has introduced a fundamental source of inconsistency in how applications are examined and disposed of.

The Thirteen Key Positions Open

The breadth and depth of current USPTO vacancies underscore the magnitude of organizational change:

Commissioner for Patents

Commissioner for Trademarks

Chief Administrative Trademark Judge

Deputy Commissioner for Patents

Director of the Office of Enrollment and Discipline & Deputy General Counsel

Deputy Solicitor of the USPTO and Deputy General Counsel for IP Law

Chief Administrative Officer

Chief Financial Officer

Chief Information Officer

Director of Governmental Affairs and Oversight

Chief Policy Officer and Director of International Affairs

Chief Artificial Intelligence Officer

Chief Technology Officer

The absence of stable, experienced leadership at these critical levels is not incidental to the changes we are witnessing; it is foundational to them.

Part 2: The Two-Tier IP System and the Inconsistency Problem

The managerial and structural changes outlined above have created what can only be described as a two-tier patent system, one that threatens to undermine the very consistency and predictability that practitioners and applicants depend upon:

Three Classes of Patent Examiners

Traditional examiners operating within art units under supervisory review

"Personalist" examiners with undefined roles and AI development obligations

SPEs and QASs who examine patent backlog applications without any apparent quality review oversight

Two Classes of Applications

Applications assigned to art units by class/subclass and examined by traditional examiners

PBAs assigned to SPEs, quality assurance specialists, and group directors—examined without quality review

Some traditional examiners are also assigned to PBA work, creating a hybrid model

Patent applicants have no choice in how their applications are examined

Two Types of Applications (by Processing Speed)

Expedited applications under Track One, PPH, age of inventor, health of inventor, or the new Streamlined Claim Pilot program: First office actions expected in months

Un-expedited applications: Enduring long wait times for first office actions, with wait times now measured in years for many technology centers

Two Types of Quality Review

Traditional OPQA (Office of Patent Quality Assurance) reviews, now likely disbanded or severely diminished, as reviewing QASs are assigned examination tasks

Supervisor-performed quality review of merits for all independent claims, creating inherent conflicts of interest given supervisors' own examination obligations and a tendency to show their art unit is producing high-quality work.

This fragmentation creates a fundamental problem: inconsistency. The same type of invention, presented by different applicants at different times through different examination pathways, may receive vastly different treatment. For practitioners advising clients, this inconsistency introduces unpredictability into prosecution planning.

The Mathematics of the SPE Review Problem

A typical SPE supervises 13 patent examiners, 7 of whom are primaries. On average, this amounts to about 12.5 additional hours of work per biweek for each SPE.

Reductions in clerical support staff will add further delay to the mailing process.

The inevitable result: delays in mailing office actions, compressed quality review, or an inconsistent, selective approach for the review mandate.

It bears noting that these sweeping changes are not being implemented consistently across the agency. While the stated policy has been to move RCEs and continuing applications to the back of the docket, anecdotal reports from practitioners indicate that some RCEs are nevertheless being picked up for immediate examination, creating further unpredictability in prosecution timelines and strategic planning.

An example of the new SPE review window is provided below:

Prior to these changes, this final office action would likely have been mailed in a couple of days. Now, new quality review delays can push mailing back by weeks.

Practitioners should anticipate what we term "mortgaged" applications, those held in examiner or supervisor queues awaiting review, creating new prosecution windows and tactical opportunities. For example, slow supervisor review can create opportunities to file IDSs without having to file a Request for RCE.

Part 3: Implications for Applicant Strategy

What Practitioners Can Expect

Armed with an understanding of the structural pressures now facing patent examiners and supervisors, practitioners should anticipate the following:

Reduced opportunities for interviews: Examiners have been constrained to one hour per prosecution round. Practitioners must be highly strategic about interview deployment. We recommend reserving interviews to address substantive rejection bases (e.g., anticipation, obviousness) rather than procedural issues. Providing a telephonic election to a restriction requirement could be counted as the application's only interview opportunity. Instead, practitioners can ask that the restriction requirement be sent in writing.

Challenges in post-final prosecution: The expiration of AFCP 2.0 and the operational pressures on SPEs have made continuation of prosecution after final rejection increasingly difficult. An RCE now faces the risk of being moved to the back of the backlog rather than being prioritized for prompt reexamination.

Expect extensive delays in the examination of RCEs and continuation applications.

Delays between office action count and mail dates: Given the SPE review bottleneck and reduced support staff, practitioners should anticipate that office action counts appear in the prosecution transaction history, but corresponding mail dates lag significantly. This creates opportunities for strategic Information Disclosure Statements (IDSs) and other procedurally timed filings.

First-action allowances and ex parte Quayle actions: The most straightforward way for examiners to meet production and pendency targets is to allow claims. Practitioners should prepare for a higher frequency of allowances, but often conditioned on procedural corrections (ex parte Quayle actions) rather than substantive amendments. These ex parte Quayle actions raise procedural objections while allowing claims, requiring close attention to administrative detail. Practitioners should prepare for these first-action allowances by filing preliminary claim amendments, reviewing for correctness of procedural items (e.g., priority claims, Applicant Data Sheet, inventorship, etc.), prepare and file IDSs as soon as possible after filing to make prior art of record, prepare and file assignment documents, review claims for obviousness-type double patenting issues, and file a terminal disclaimer or petition to withdraw a terminal disclaimer if necessary, and prepare claims for continuation applications.

Unusual allowance patterns: Expedited applications are seeing higher allowance rates, potentially reflecting the pressure on examiners to clear backlogs and meet pendency metrics. Examiners, now including SPEs and QAS, may be emboldened to process patent backlog applications quickly, assured that no apparent quality review will take place.

File IDSs that list all related patent applications to create a clear and complete file record with respect to double patenting concerns.

Tactical Guidance: Maximizing the New Environment

For expedited applications (Track One, PPH, age/health, Streamlined Claim Set Pilot Program):

Prepare claims for allowance from the outset. Ensure claims are drafted with maximum clarity and specificity to survive 35 U.S.C. §§ 102, 103, and 112 scrutiny.

Review procedural fundamentals: Verify priority claims are correct, assignments are correctly documented, inventorship is accurate, and all administrative details are in order.

Plan for continuation applications: Prepare a continuation strategy to capture additional claim scope. Should an expedited application issue as narrower than desired, continuation applications can follow with knowledge of the examiner's position.

Address double patenting proactively: File terminal disclaimers or initiate petitions to withdraw terminal disclaimers as warranted, before receiving allowance notices that may contain unexpected double patenting conclusions.

File IDSs strategically: Given the lag between action counts and mail dates, practitioners can file IDSs during this "mortgaged" application window, ensuring prior art is made of record without triggering an RCE or loss of patent term adjustment. An IDS filed before the mail date of a first office action does not require a fee or statement of certification.

For non-expedited applications:

Leverage the SPE review window: The 30-minute supervisory review requirement creates a window of opportunity. Between the examiner's action and the SPE's review, there is a tactical window for filing IDSs that will be made of record without forcing an RCE or backlog reassignment, or resulting in a reduced patent term adjustment.

Be surgical with interviews: Use the single permitted interview hour to address the strongest basis for rejection. Do not waste this opportunity on procedural niceties.

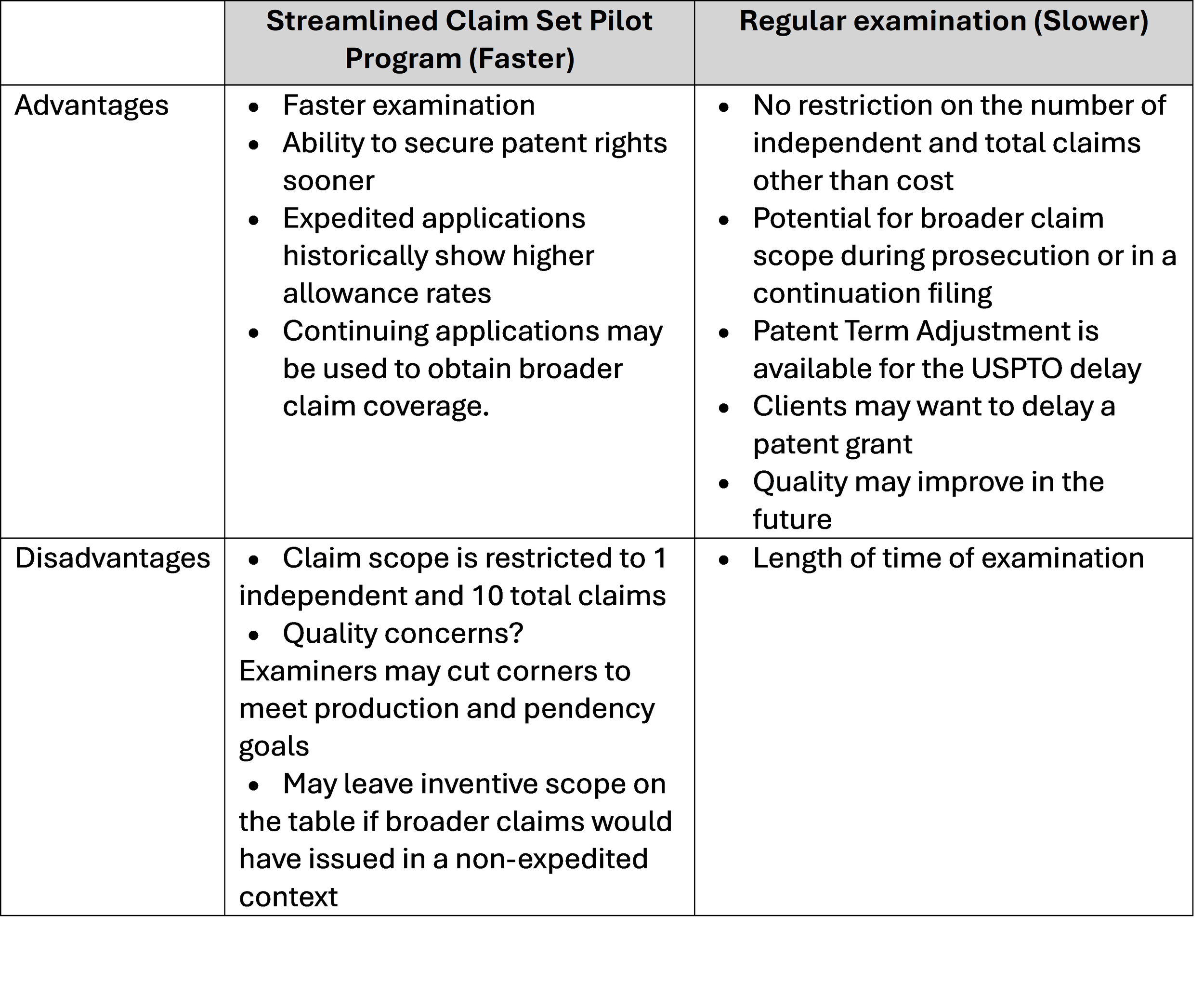

Consider application tier selection carefully: The Streamlined Claim Pilot Program, while limiting claims to 1 independent claim and 10 total claims throughout prosecution, offers expedited treatment. For specific applications (narrow, well-defined inventions), this may be an acceptable tradeoff.

Non-expedited applications can obtain significant amounts of patent term adjustment, which may be of great value for certain inventions.

Setting Up Docket Status Notifications

To navigate this new landscape effectively, practitioners should implement robust docket management tools:

MyUSPTO Patent Docket Widget Status Change Notifications:

Log in to MyUSPTO

Click on "Home actions" and add widgets

Under the Widget library, select "patents"

Create a collection of patent applications for which you wish to receive status notifications

Enable email notification of status changes

By implementing these notifications, practitioners gain real-time visibility into application status changes, enabling rapid response in advance of office actions, allowances, and other developments.

Part 4: The Backlog Crisis and Wait Time Realities

Scale of the Problem

An analysis of USPTO data reveals the magnitude of the backlog challenge:

USPTO published statistics indicate a 22.6-month average wait time for a first office action. But the actual average wait time for a first office action varies dramatically by technology center and application type. Applications submitted to specific technology centers (particularly those handling biotech, pharma, and complex electrical technologies) face extended wait times.

The wait times for applications are as follows:

Track One applications: Approximately 4-6 months average. In some tech centers, Track One applications make up more than 25% of newly filed applications. These all jump to the head of the line.

Expedited applications (PPH, age/health, Streamlined Claim Set Pilot): 4-6 months average

Non-expedited applications: Varies significantly by technology center; many technology centers now face 18- 30+ month waits for first office action. First office actions mailed more than 14 months after filing can result in a significant patent term adjustment.

The disparity between expedited and non-expedited examination has widened substantially. The graph below shows an estimate of the technology center's average wait time for a first office action in a non-Track One application versus a Track One application.

The Patent Prosecution Highway Program

Before these sweeping management changes, the PPH had offered an average 4-month prosecution window for the first office action. China is the USPTO's most frequent PPH filer. Perhaps in an attempt to level the playing field, all PPH applications now face docketing delays. Practitioners should now expect the wait time for the first office action to be half that of a non-expedited application. This change means that the average wait time for a PPH first office action could be as short as 11 months (in technology center 3600) or as long as 17 months in technology center 1600).

The most common path is to file a PCT application requesting a European Search report, then file a PPH with the USPTO.

The USPTO receives about 8,500 PPH applications per fiscal year, about 1.8% of its annual filings. Given this, for fiscal year 2026, the examiner's performance and appraisal plan (PAP) has adjusted the count value for PPH applications to 1.5, down from 2.0 for fiscal year 2025. This means examiners are given 25% less time to examine a PPH application as compared to a non-PPH application. Given the reduced PPH count, this change will likely result in more lightly examined first-action allowances. First action allowance rates for PPH applications are already approximately twice those for non-PPH applications. Historical data from FY 2022 showed PPH applications enjoyed an overall 88% grant rate.

The Streamlined Claim Set Pilot Program: A New Tactic

The USPTO has introduced a tactical option worth serious consideration: the Streamlined Claim Set Pilot Program. Practitioners can move unexamined applications out of the backlog with a focused claim set approach.

Requirements:

Original, unexamined utility applications filed under 35 U.S.C. § 111(a)

Currently pending applications qualify for this program as long as the request is filed before a first office action

Limited to 1 independent claim and 10 total claims

The streamlined claim set can be filed via a preliminary amendment, protecting the effective filing date of originally filed broader claims.

Claim limits apply throughout prosecution

Requires petition (Form PTO/SB/472) and associated fee

Limited to 4 total applications per inventor or joint inventor

Limited to first 200 applications per technology center

Tradeoff Considerations:

Overall assessment: The Streamlined Claims Pilot is strategically sound for well-defined inventions where a narrow claim scope is acceptable, or as a defensive measure to secure some patent protection. In contrast, broader claims are better prosecuted using conventional examination and continuation applications.

Part 5: The 101 Revolution—Director Squires Opens the Door to Innovation

Director Squires' Decisive Action on Day One

On his first day as Director, John Squires took symbolic but meaningful action, signing patent applications for:

U.S. Patent No. 12,419,201: Methods for Histochemical Assays for Human Pro-Epiregulin and Amphiregulin

U.S. Patent No. 12,419,202: Systems and Methods for Generating an Architecture for Production of Goods and Services

These signings were not administrative formalities; they were a statement of a new direction regarding patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

The 101 Reversal and Desjardins

Shortly thereafter, Director Squires reversed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board's decision in Ex parte Desjardins (Appeal 2024-000567, decided September 26, 2025), which had applied a restrictive approach to 35 U.S.C. § 101 eligibility.

This reversal signaled a fundamental reorientation of the Office's approach to patent eligibility, moving away from the restrictive positions that have prevailed in recent years toward a more permissive framework for inventions in emerging technology areas, particularly biotech and computer-related innovations.

The Three Pillars of Patent Eligibility

On Halloween 2025, Director Squires articulated his vision in a keynote address to the American Intellectual Property Law Association. His "Three Pillars of Patent Eligibility" framework provides practitioners with a roadmap:

Pillar 1: 35 U.S.C. § 100(b) Applicability

Section 100(b) defines a "process" as encompassing "a new use of a known or old device, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material." This pillar restores emphasis to novel applications of known compositions and methods—critical for pharmaceuticals, biotech, and chemical innovations where the underlying compounds may be known but the clinical application is novel.

Pillar 2: Computer-Related Innovations and Data Structure Improvements

The Enfish decision held that improvements to computer data structures constitute patent-eligible subject matter. This pillar affirms that claims to software, algorithms, and digital innovations that produce a tangible, technological benefit are patent-eligible. For biotech companies employing computational biology, bioinformatics, and AI-driven drug discovery, this is a significant green light.

Pillar 3: Non-Obvious Technical Effects

Claims that survive 35 U.S.C. §§ 102, 103, and 112 and confer something more, what Director Squires termed "something Morse", are patent-eligible. The reference to Morse harkens back to Samuel Morse invention of the telegraph in 1840. It invokes the historical principle that an invention producing a previously unknown technical effect is patent-eligible.

PTAB Response and Petition Office Grants

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board has responded to Director Squires' signal with a series of 35 U.S.C. § 101 reversals. Moreover, the Petitions Office has begun granting petitions to revive abandoned applications where the only basis for rejection was 35 U.S.C. § 101. This represents a significant shift: Previously abandoned applications may now be revivable.

Strategic Implications for Practitioners

For applications abandoned solely on 35 U.S.C. § 101 grounds:

Consider filing a petition to revive under 37 C.F.R. §§ 1.137 or 1.138, combined with a request and revival fee.

If revival is granted, consider filing an amendment or RCE advancing arguments grounded in Director Squires' Three Pillars.

Consider potential ethical implications for reviving unintentional abandonments and the option for filing a petition under 37 C.F.R. § 1.183 to waive or suspend rule in extraordinary situations.

For pending applications with 35 U.S.C. § 101 rejections:

Frame arguments in terms of the Three Pillars: novel process applications under § 100(b), technical improvements to data structures or algorithms under Enfish, or technical effects that survive 102/103/112 scrutiny.

For pharmaceutical and biotech applications, emphasize novel therapeutic uses, dosing regimens, patient populations, or combination therapies, all of which fit squarely within Pillar 1.

For newly filed applications:

Draft specifications and claims with explicit emphasis on technical effect and non-obviousness. Highlight the specific, technical problem solved and the unexpected result achieved.

For software-related innovations, claim not merely the algorithm but the data structure improvements or system architecture that produces the technical benefit.

Part 6: The Eternal Tension—Quantity vs. Quality and the Historical Context

Commissioner Ooms' Prophetic 1945 Memo

Eight decades ago, an obscure but prescient USPTO Commissioner, Ooms, confronted the same tension that now faces Director Squires. In a 1945 memorandum, Commissioner Ooms observed:

"It has been brought to my attention that the practice prevails in the Patent Office of measuring the 'amount of work accomplishedby Assistant examiners and subsequently rating the efficiency of Examiners in this respect by the number of applications finally disposed of, as by abandonment or allowance. This practice necessarily emphasizes quantity rather than quality of work."

Ooms continued, offering wisdom that resonates across the decades:

"Work of the kind in which Patent Office Examiners are engaged required great public and private interests, and requires exceptional training and experience coupled with matured and considered judgment in its execution. For these reasons, it cannot be measured by methods applicable to routine office operations."

And most powerfully:

"High class professional work performed in a favorable environment and adequately compensated inevitably attracts and hold high class men, and the pride of achievement entertained by such men ordinarily provides a sufficient incentive for work which is commendable both as to quality and quantity... Accordingly, the quota system is hereby abolished and all order in conflict herewith are hereby rescinded."

The Triangle Without a Solution

Ooms understood something fundamental: The triangle of Production (volume), Pendency (speed), and Quality cannot be resolved. You can achieve two, but the third must give way.

The current crisis at the USPTO reflects a fundamental misalignment between metrics and reality:

Production is rising as examiners rush to process applications and meet action count targets.

Pendency is improving for expedited applications, and backlogs appear to be declining.

Quality is declining, as evidenced by compressed examiner interview time, the elimination of mentoring, the removal of quality assurance specialists from review roles, and the implicit acceptance of zero-quality-review PBAs.

The current approach mirrors the quota system that Commissioner Ooms abolished in 1945. History suggests this will not end well.

Key Takeaways for Patent Practitioners

As we navigate this uncertain landscape, we offer the following distilled guidance:

1. Understand the Two-Tier System

There is no clear-cut way to determine whether your application is being processed as a traditional application or a PBA. Some PBAs can be identified by being assigned to SPEs or QASs who traditionally have not examined patent applications. Others will be assigned to traditional examiners who understand that, if it is a PBA, an abbreviated examination will not be subject to quality review. This is not inherently problematic, but it changes your prosecution strategy.

2. Be Strategic About Expedited Prosecution

Track One, PPH, age/health expedited prosecution, and the Streamlined Claim Set Pilot Program offer pathways to faster examination.

Track One offers 4-6 month average timelines to first office action and historically higher grant rates.

PPH now offers an average 11-17 month timeline to the first office action and historically higher grant rates.

The Streamlined Claim Set Pilot Program sacrifices claim breadth for speed, appropriate for certain applications but not all. This pilot can be used to move an original, unexamined application out of the backlog.

Non-expedited applications now face 18- 30+ month waits in many technology centers. Consider the cost-benefit of expedited options for your clients.

3. Plan for First-Action Allowances

Draft claims defensively, anticipating allowance, to ensure they are robust and well-supported by the specification.

Prepare continuation applications in advance to capture additional scope.

Address double patenting issues proactively.

File IDSs strategically during prosecution windows.

4. Leverage the SPE Review Window

The mathematical impossibility of the SPE review mandate creates prosecution windows.

File IDSs after examiner action but before SPE review and office action mail date, and you may avoid RCE, PTA losses, and backlog reassignment consequences.

Use your single interview hour carefully for substantive rather than procedural issues.

5. Capitalize on the 101 Reversals

The Three Pillars framework opens previously closed doors.

Consider reviving abandoned applications that failed under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Frame pending 101 rejections using the Pillars: novel processes under § 100(b), technical improvements under Enfish, or non-obvious technical effects. Provide arguments consistent with ex parte Desjardins.

6. Monitor the Organizational Instability

13 critical USPTO positions are open with no clear timelines for filling them.

Leadership vacancies create uncertainty, but also an opportunity for practitioners to influence the Office's direction through comments and advocacy.

The current trajectory may not be sustainable; prepare for further changes.

7. Implement Robust Docket Management

Set up MyUSPTO status notifications for all active matters.

Monitor delays between action count and mail dates.

Anticipate "mortgaged" applications and plan procedurally accordingly.

8. Maintain Perspective on Quality

The current environment creates incentives for examiners to approve applications without thorough examination.

This may accelerate prosecution in the short term, but may create problems in post-grant proceedings and litigation.

File IDSs that list all related applications and patents to create a clear record with respect to double patenting.

Consider whether the various accelerated timelines truly serve your client's interests or merely appear to do so.

Conclusion

As of November 2025, the USPTO is an institution in transition—undergoing the most significant structural and operational changes in decades. Patent practitioners must adapt their strategies to account for new realities: bifurcated examination pathways, reduced examiner resources, compressed review cycles, and a fundamentally more permissive stance on 35 U.S.C. § 101 eligibility.

The changes offer both opportunities and risks. Practitioners who understand the structural pressures facing examiners, strategically deploy expedited examination, prepare their claims and continuations in advance, and leverage the new 101 framework will position their clients to maximize patent protection. Those who proceed with conventional prosecution strategies developed for a different era may find themselves at a disadvantage.

History, as Commissioner Ooms' wisdom from 1945 suggests, suggests that the current trajectory is unsustainable. Quantity and speed cannot forever substitute for quality and considered judgment. The pendulum may swing again. But for now, practitioners must work within the system as it exists, understanding its pressures, exploiting its opportunities, and maintaining watchful skepticism about whether the apparent gains in speed and expedience will withstand the test of time.

The patent landscape has shifted. Our duty is to help our clients navigate it wisely.

This post was written by Lisa Mueller and Julie Burke.